I’ve learned so much about deep PoV in the past three years, thanks in no small part to Jeni Chappelle and Maria Tureaud for sharing their wisdom. As it’s something I’ve passed on to my writing group so we’re all constantly poking at each other about it, and as it’s something I noticed when going through WriteMentor submissions, I thought I would write a blog post about it to give my two cents on deep PoV, internals, and how they can elevate your manuscript.

First off, what actually is deep PoV and why should you use it? Or should you even use it? I don’t subscribe to very many “you should always do X” thoughts on writing, because I think so many of the rules of writing are really more like guidelines. (Yes, I know it shocks absolutely nobody that I’m a pirate at heart.)

Deep PoV is popular right now for great reasons–it’s doable in any PoV except omni (and even then we can bring the omni in close with it), and it naturally creates tension and shows change. It creates a scenario that puts the reader in the point-of-view character’s head, riding along with everything they’re thinking, feeling, etc. It just takes a little practice to really get the hang of.

As such, I heartily recommend Rivet Your Readers with Deep Point of View by Jill Elizabeth Nelson especially if you’re struggling with it but even if you have a grasp of the basics and just need another handhold up. I skimmed the beginning because I was familiar with the basics when my critique partner KJ Harrowick recommended this book to me, but then by the end I had so many Aha! moments. It’s really become something that fundamentally changed my writing outlook, and as such, I recommend this book to tons of writers because it has so much knowledge packed in such a short book with exercises that actually make sense and don’t feel like busywork.

So how do we do deep PoV in a nutshell? First, get rid of all that filtering that’s not necessary anyway–you’re gonna need those words for your internals. So all those times your character looks, sees, hears, feels, smells, etc? More than likely they’re unnecessary because you can just describe what the character is sensing, since we’re in their head.

Second (for me–remember, this is deep PoV in a nutshell, not the whole bag of peanuts), pay attention to your internals and use them wisely. Internals are just those responses and reactions that are inside the character–you can’t necessarily see them from outside (though when we use body language we can then infer emotions). So, emotions get put here, especially if you’re naming them, and so do thoughts, viscerals, and body language cues.

When working with emotions, keep in mind the character’s age. It’s not that you get more emotions in younger characters, but their reactions to the emotions change. So a frustrated toddler might faceplant in the middle of the store aisle and wail, while an older child might cross their arms and stomp their feet, and a teenager sigh. An adult might keep that frustration entirely internal, so then you’d use thoughts/emotions/viscerals to show that in deep PoV.

The characters’ reactions should also change as the character develops, so keep in mind where they are in their development arc when you’re adding reactions. You might have the same visceral reactions or reflexes, but the thoughts should change and eventually, their decisions. This was huge when I learned it. There’ll be more about this in a bit.

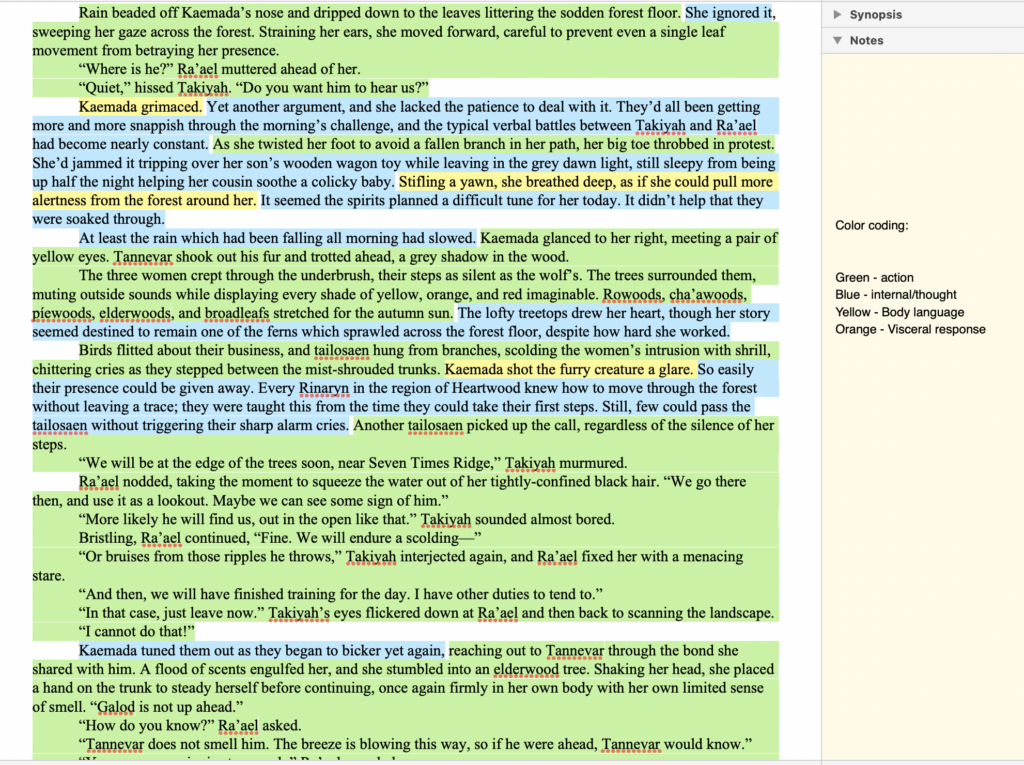

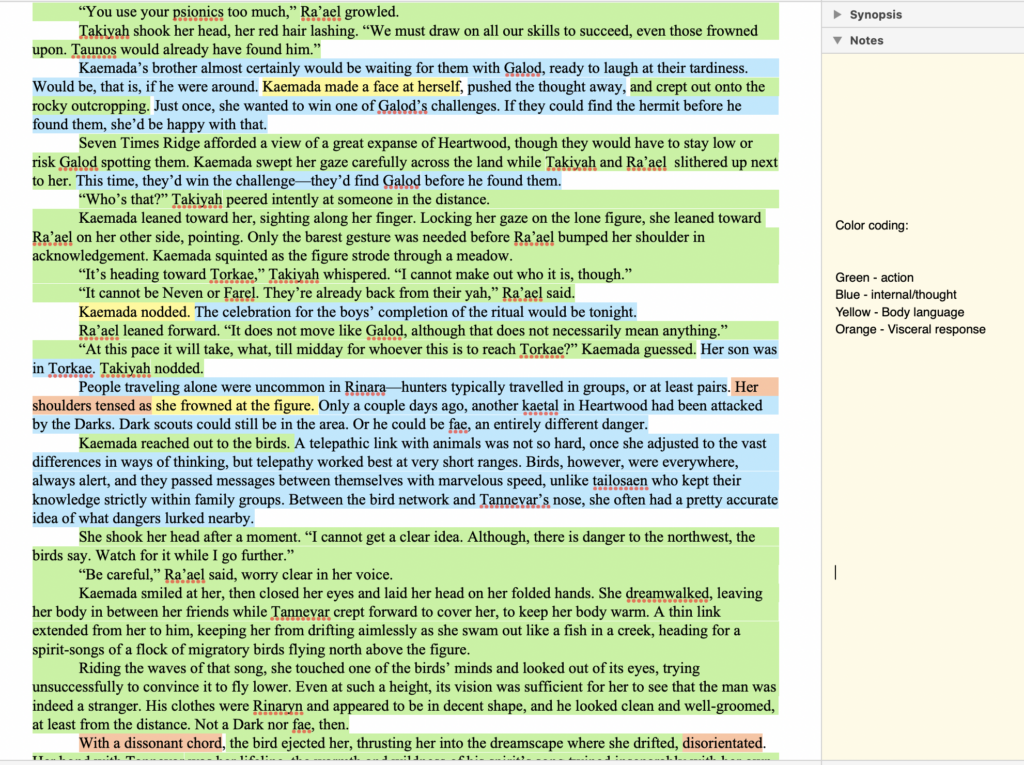

One thing I did, since I tend to work best when I can see everything at once, is color-coded all my internals so I could weave them in best. The internals are all coded to the PoV character because their perspective is the only one that matters for this. They’re the only one who can give internals in deep PoV.

You can see most of my writing here is green–those are descriptions, other characters, and things that can be seen. If it were a tv show or movie, much of the green would still come through (blue and orange, however, would be lost). Internals naturally slow down the pace of the scene, because much of the pacing comes through from the green. So rather than clump up the internals, I started learning to sprinkle them in like seasoning–or commas! Because everyone knows commas are seasoning, right? XD

Ok but seriously, if you have too big a chunk of blue or orange, it’s going to feel slow and like nothing’s happening. Spicing it up with yellow helps, especially if you can’t do much green due to the scene’s constraints (maybe your character is tied up and can’t move. They can try to move though, giving you some green, even if they don’t succeed, but you’ll still want to break up any thoughts with action or other internals so you don’t have pages of naval-gazing bogging down your plot. This was a bit time-consuming, but once I got a feel for it, I started to just be able to guesstimate where the next internal should be and no longer needed to color code.

I highly recommend taking the time to color code, especially if you’re having trouble balancing emotions and plot! Sometimes it’s true that your writing is feeling too emotional, but other times it might be that your writing’s emotions are simply too repetitive or not expressed in a way that feels age-appropriate.

The internals will help to really show your characters’ movement along their arc, too. Even if their choices are the same through the first half of the story, if the reasoning changes that can still feel like movement. And then eventually the reasoning no longer matches the choice and you get a new choice made– ta-da! Growth!

MRUs are Motivation-Reaction-Units and I learned about these from both my Writer In Motion friends and from my critique partner R. Lee Fryar. They’re input/output cycles, or external-internal-external cycles, as I think of them, and they were first described by Dwight Swain in 1981 in Techniques of the Selling Writer. It took me a little bit to work them out, but I’m starting to feel like I have a handle on them. KM Weiland’s blog post really helped me make progress in understanding them, so definitely check that out. This blog post also made its way into my resources! And so did this one!

For MRUs, in short, you have an action–something that happens to your character or around them. That action/event sparks a reaction–and often this reaction is really a chain of reactions. If the chain doesn’t occur in the right order, it can feel overdone, like you’re hammering on emotions, or like your character is over-reacting or reacting in a delayed manner. Feelings and visceral reactions (including reflexes) happen first. Then thoughts. Then actions, then speech. So we have internals leading us into rationalizing a course of action, and then carrying it out. If you think back to the last time you were surprised, speech tends to be one of the last things that come back to us (because the speech centers involve the cortex, while the limbic system drives emotion-field reactions). When I’m talking speech here, I don’t mean shouts of surprise or swearing–of course that can happen right away. But here, I mean rational speech (which can be merely rationalizing the decision already made/action already taken).

Sometimes it helps me to write things out multiple times, so here’s three different ways I wrote it for myself:

Motivation – Visceral/Body Language/Feeling – Thought – Physical Action – Speech

Action-Reaction-Processing-Decision-Action

Stimulus (action), reflex reaction, processing (longest, emotions in there), decision making, new action.

So MRUs actually demonstrate the importance of where you put what type of internal. If you put a reaction after reflection, it’s going to feel off to your reader. Maybe it’ll just be confusing, or maybe your character will seem a little unhinged. You don’t want your reader confused because that hinders their emotional involvement, and we really want to capitalize on that in deep PoV. That’ll help us to keep the tension strong and keep the reader turning the page, unable to put the book down.

Hopefully some of this makes some sort of sense and helps you grow your craft!